Version tested: PC (OS X)

Available on: PC, Mac, and Linux

Developer/ Publisher: Shark Punch

Genre: Action/ indie/ strategy

Making the “greatest heist in the history of mankind” look easy in order to “stick it to the man.” Get in. Get the cash. Find any weapons or clues for future heists. Get out.

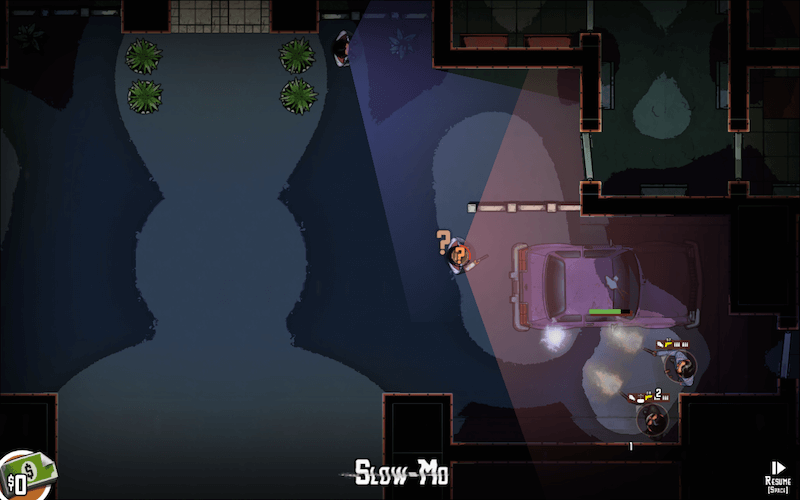

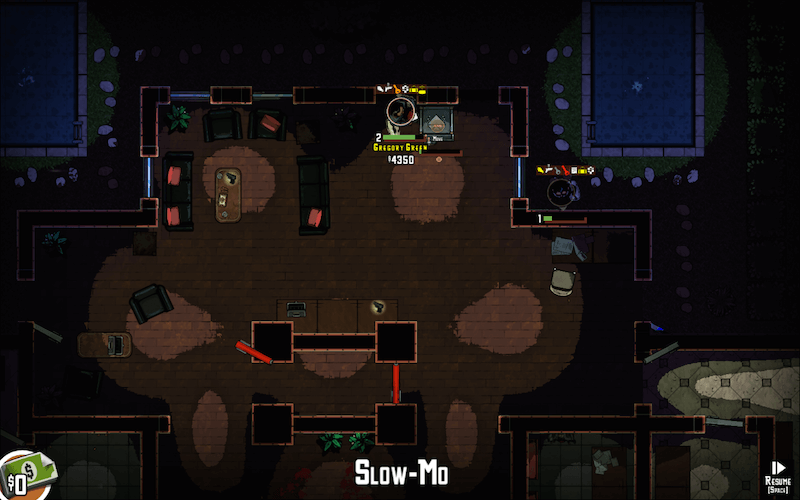

This is the premise of Shark Punch’s 70s-era, tactical heist game The Masterplan. With snazzy music and a unique, cartoonish look, it mixes its own brand of humor and lightheartedness into what’s essentially a slower-paced cousin of Hotline Miami. (There’s even the same amount of flail, plus a drug-dealer in a rubber horse mask.) Called “the game that started it all” by its developers, The Masterplan marks the first release for Shark Punch studios, and merely looking at stills from the game will show you who they are and what they wanted—and succeeded—to make: A great game with its own style and its unique way of doing things.

(And this is where I warn that I’m going to be harsh in this article because I think this game has immense potential that’s already been tapped into. I’ll be harsh not for the sake of being harsh, but hoping that some worthwhile criticism will come out of it.)

Since its release in June, the scores earned by The Masterplan have been nothing to sniff at. On Metacritic.com, reception has been favorable (though the metascore hangs at 69), and on Steam its reviews balance out at “Very Positive” after a series of early-access-influenced updates. I have to agree with these and say I would rank it the same—if only for some rage-worthy issues with certain gameplay mechanics… namely, doors. (Oh, the doors!)

But more on those later. First, for those of you unfamiliar with the game:

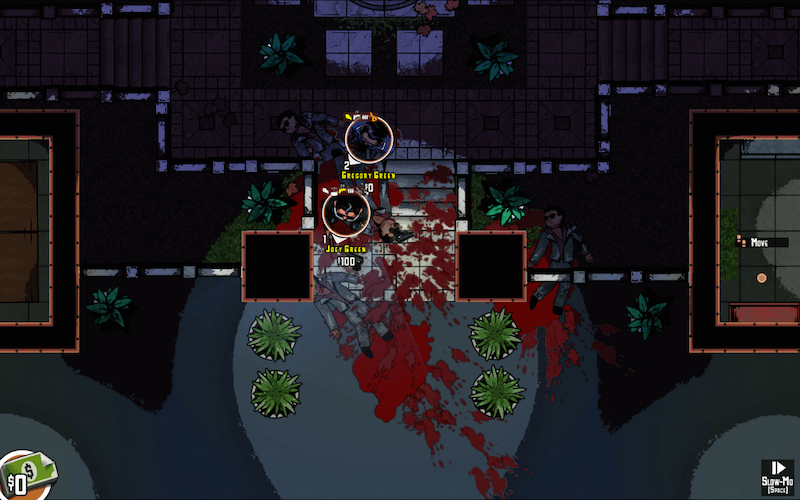

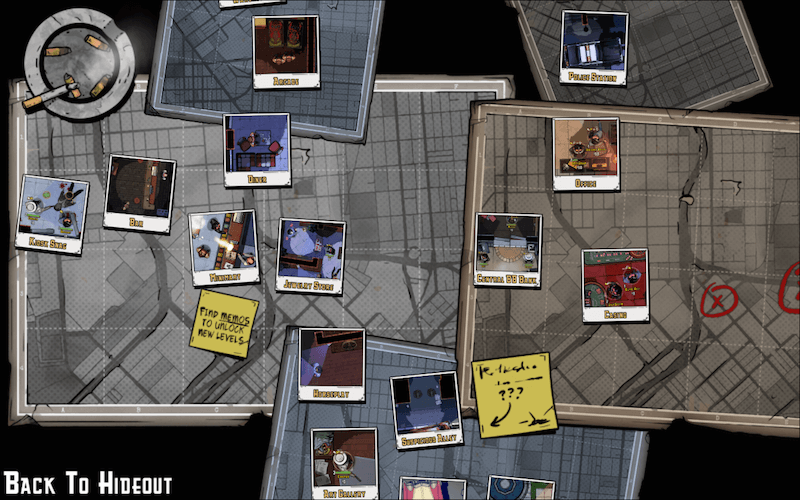

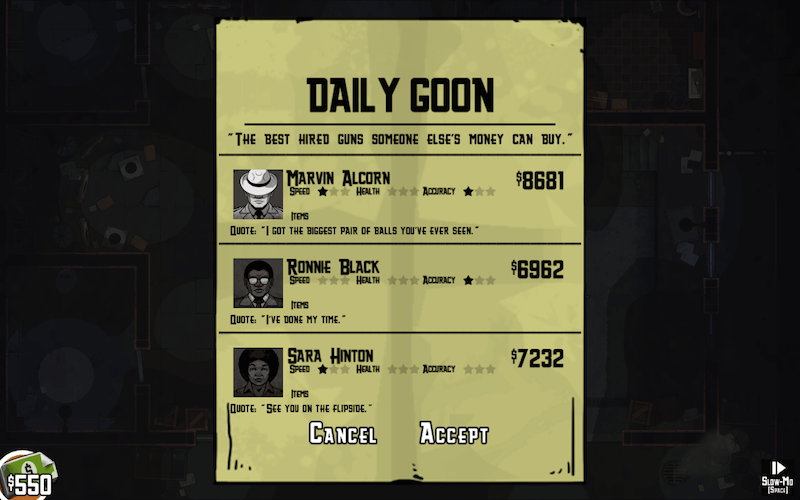

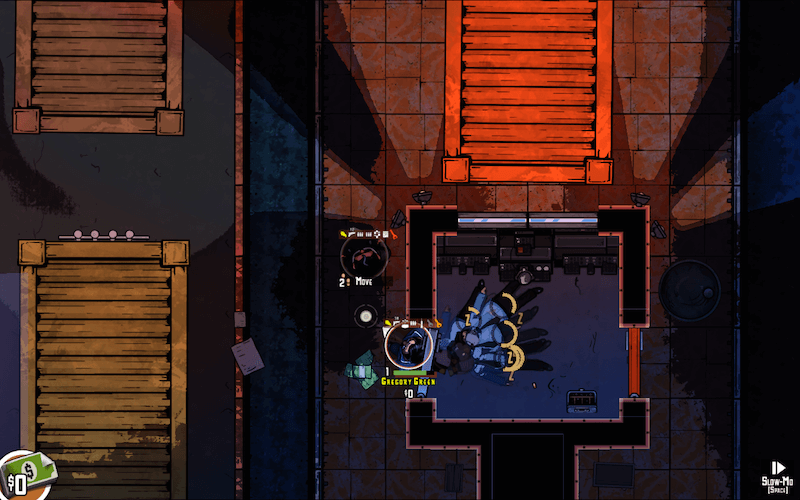

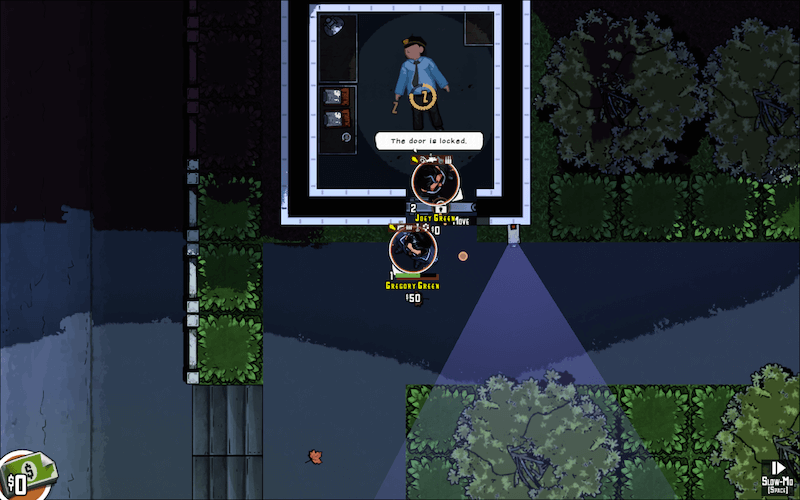

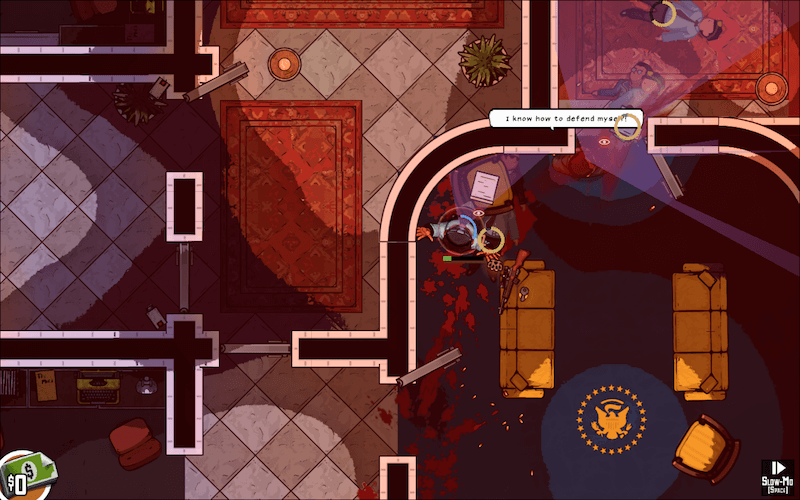

You and your two clumsy mouse buttons have full charge of two brothers, the unexcitedly named Gregory and Joey Green (or, in my book, indiscriminately Sandor Clegane and Regular-Joe Punchycuffs), and everything they do. The story goes that after hard economic times kicked them to the curb, these bros turned to crime to make a living. They battle criminal competition, corrupt cops, even the thugs of government officials (it’s set during Nixon’s term)—but most of all, they battle the man. You know, the one who’s got you down. That man. So it can’t be said the game doesn’t have a driving story, but it’s not much more than, say, Invisible Inc. has.

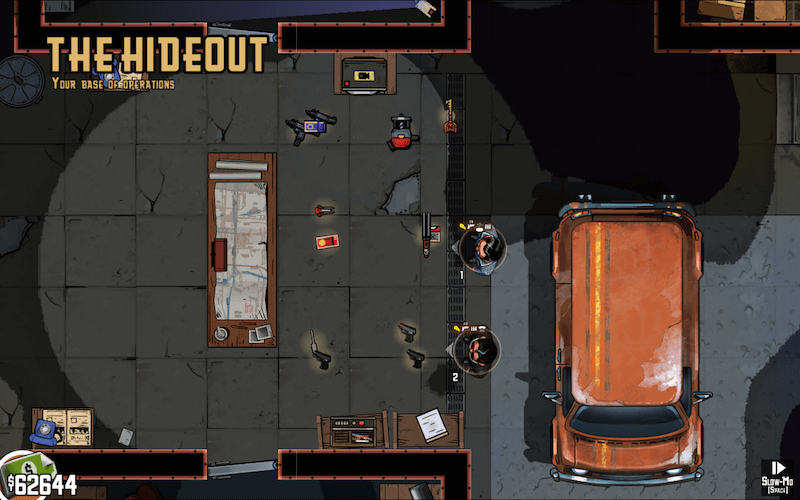

Gameplay begins with a breakout from jail, and from there a return to your old hideout, a safe-haven between heists that has a character all its own (like the rest of this world) and tells you a little bit more about how to interact with your surroundings. Hiring goons for heists, breaking fuse boxes and crates, how security monitors work, even a short gun range—it’s all there, for your convenience, to learn from. There’s plenty to play with, but on the downside, as the game progresses, aside from a few new weapons and goons to hire and more cash to spend, nothing much else comes along to play with.

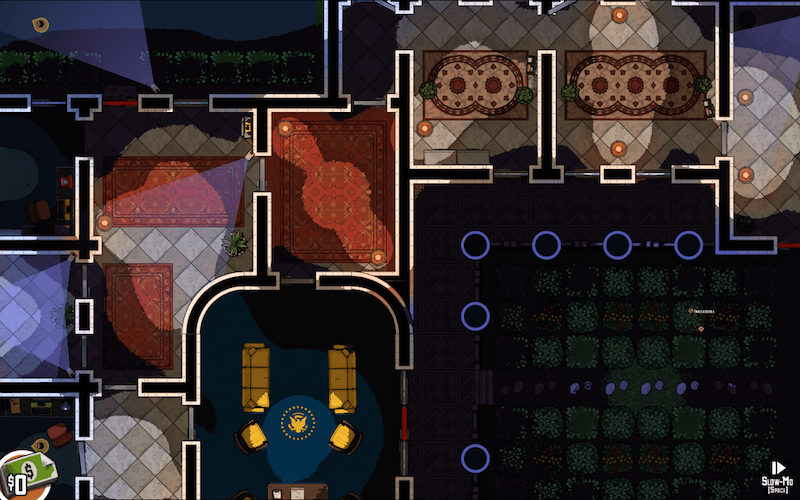

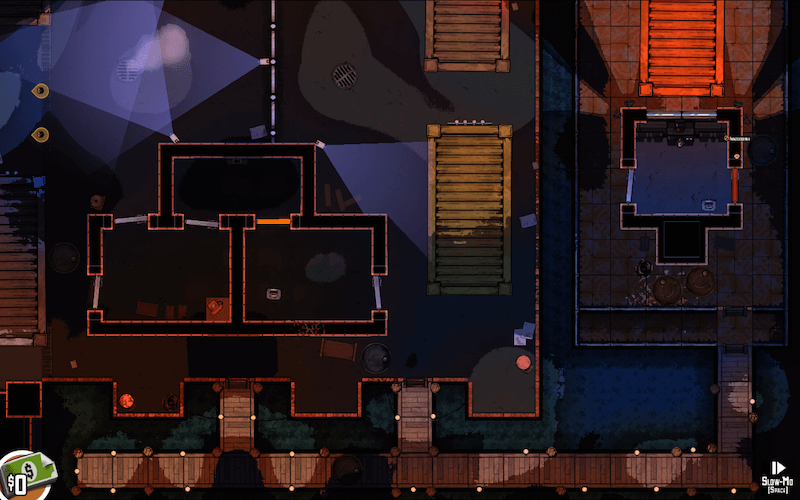

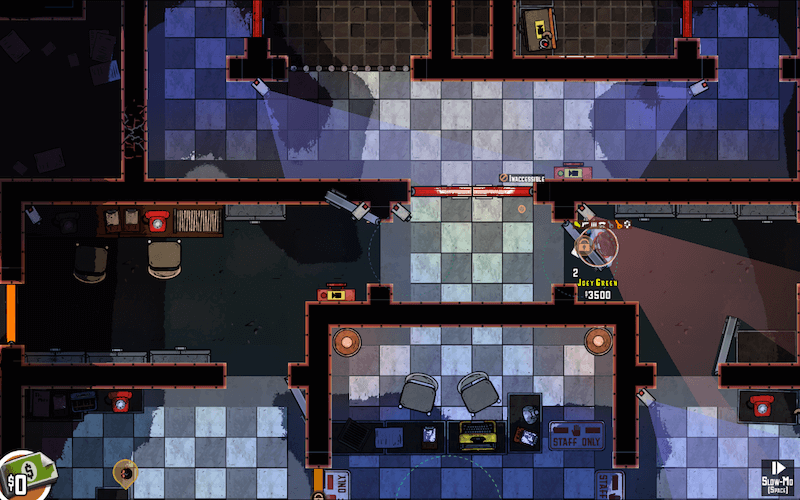

But brilliant level design makes up for whatever repetitions there are in mechanics. Like the hideout, a lot of thought clearly went into level design. With multiple ways to play each heist and clever guard placement within, crafting a master plan proves truly challenging. The first heists are against a kiosk and a bar—simple enough once you know what you’re doing—but the size and complexity of the heists steadily grow from one to the next, moving to exotic (so to speak) locations requiring greater strategy to maneuver and plunder without getting caught.

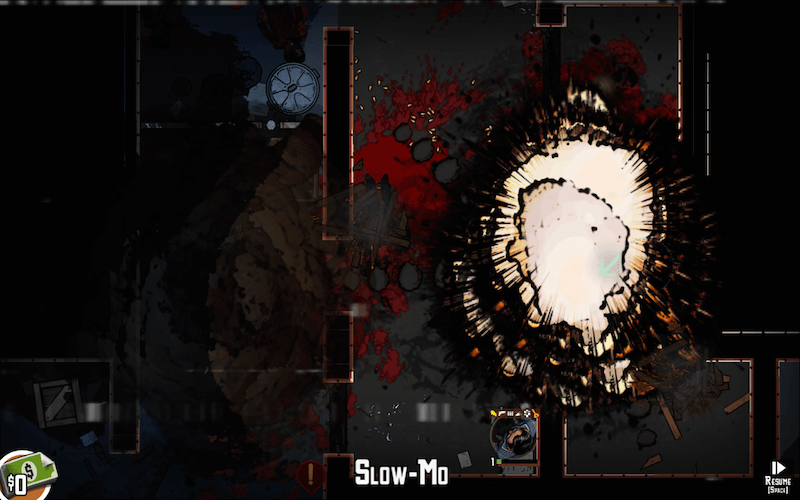

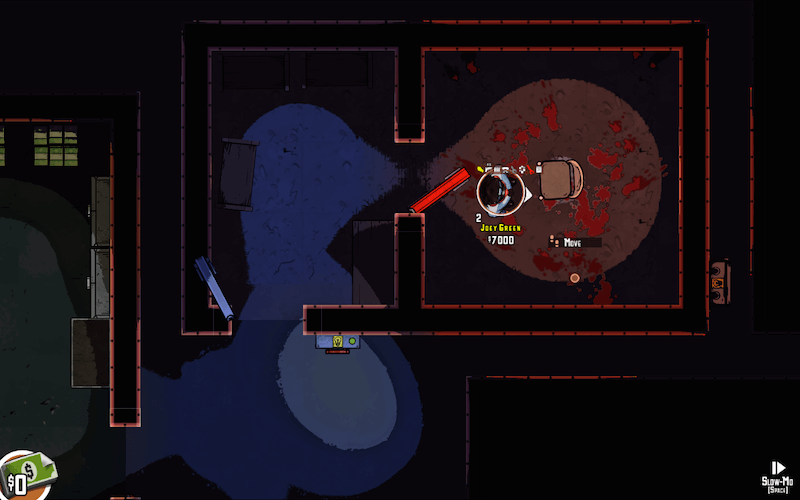

If guards hold you in their sights too long, they’ll shoot or call the cops, and then it’s almost always game over unless you act quick. I personally preferred nonlethal takedowns, but sometimes a massacre was necessary, and when guards started shooting me up, I lost my sense of mercy. I was not about to play that heist one more time! (Even though I often did because I was that close…)

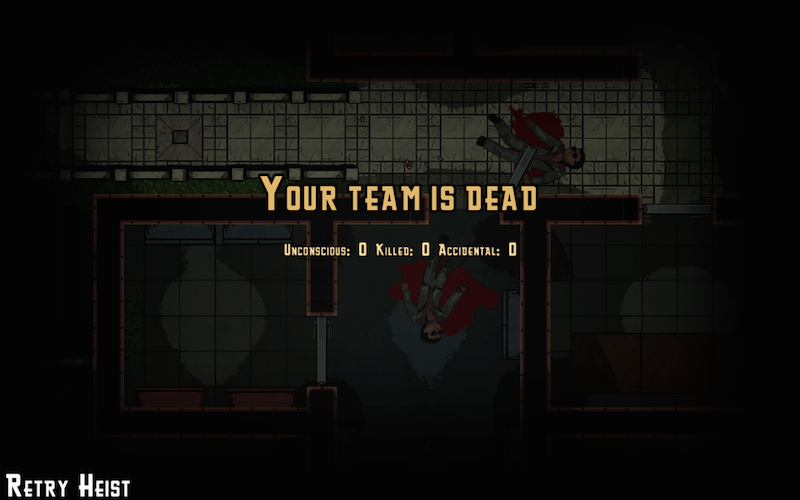

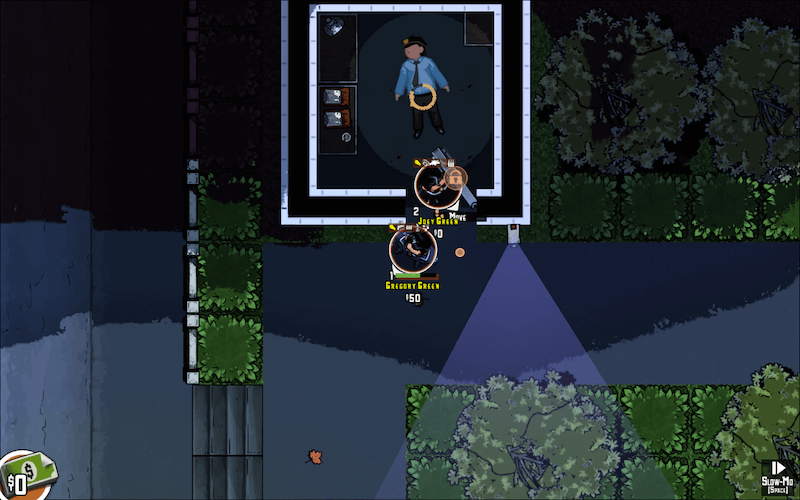

No matter how many goons you hire or how much ammo you have, it’s nearly impossible to shoot your way out of the waves of boys in blue who come once an alarm is raised. Cubbyhole rooms like bathrooms with lockable doors become your best friends. But while locking doors can be a strangely giddy, liberating, and proud moment, doors themselves were perhaps The Masterplan’s biggest downfall.

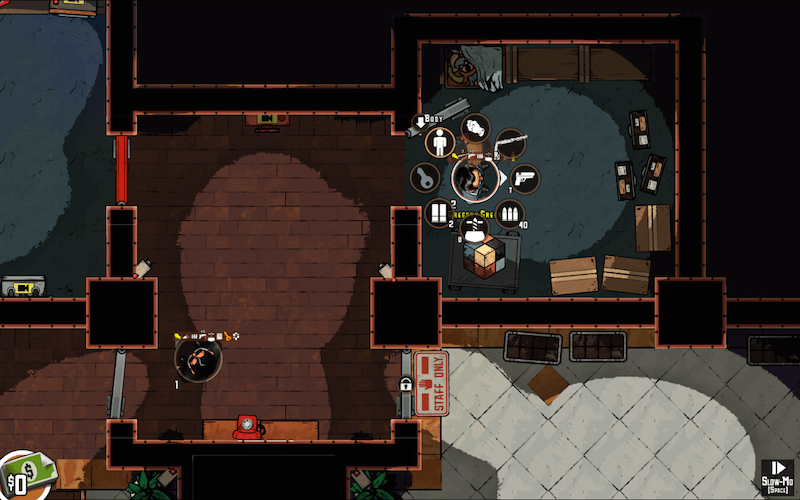

Nearly all the heists that I failed resulted from poor door mechanics. I wish I had a death montage to offer you to show succinctly just how aggravating it was trying to lock doors or even just shut them behind me to escape approaching guards—always slightly out of reach, there’s never a smooth way to close them. Some attempts ended in the door not shutting and my character coming to a halt, inexplicably deselected, and standing stock still as they alert guards and attract bullets for no good reason (restart 20-minute mission!). Or how frustrating it was having my character obstructing the door every time he tries to shut it, so he has to walk away from the door (click), then toward it (click), shut it (click click), then towards it to lock it (click shift click) (ten crucial seconds later) or else be on the wrong side of the door and lock himself inside (“Fatality!”)…

…Or have a door bounce off my character and fling wider open than before (physics!), revealing me to guards beyond and boom (dead!) when I go to retrieve it in a last-ditch effort. Or ordering a character to lock a door and he just continues to walk into it; or, in the middle of sneaking in for a take-down, you walk through a door to confront a guard in the next room and get the jump on him, but it’s too late! He’s pushing on the other side of the door, and if you step away he’ll shoot you in the back, but if you don’t turn you just keep walking against the door forever (pause-reset-heist).

…or having a door block the light that indicates an operating camera’s view without actually obstructing the footage itself, meaning I don’t know I’m being surveyed; or having a bullet propel my character around a corner out of sight, at which point he not only doesn’t step forward to shoot again but stops shooting and moving altogether as the approaching gunman regains his line of fire and takes out a statue of a man…

… Doors are basically The Masterplan’s equivalent of World War I’s “No Man’s Land.” In short, it was almost enough to make me not play the game. Sneaking was so essential that being slapped around by doors like a fish to the face tore the games’ redeeming or plain fantastic qualities to bits. It simply felt unplayable in those moments when door trouble got me killed. Over. And over. And over.

Plus, there’s no reviving a character. Unlike guards, if you’re taken down by fists and not bullets, you lose Joe Punchycuffs and/ or Sandor Clegane.

Moreover, the controls are almost entirely mouse-based (click to select, right click for everything else), the only exceptions being WASD camera movement, C to cancel a command, and Space to enter slow-motion mode for planning moves (crucial). Because of this, I found myself repeatedly giving incorrect commands without realizing it. Or I had a character repeatedly deselected instead of doing what I asked because a click didn’t register. Character deselection and immobilization happens occasionally after picking up items, as well.

Before I knew about the slow-mo feature that allows you to plan actions before the brown stuff hits the fan, the time delay between moves was a game-ender every time. Even with the slow-mo feature, having to reselect your character became tiresome and couldn’t always be done by pressing “1” or “2” (which it’s never taught you can do) because sometimes, randomly, these becomes “3” and “4.”

What first drew me to The Masterplan was its concept and art style. I wanted to execute the best heists ever in this fun-looking world. I felt like I could—if only the game would let me carry them out. For the most part, it did. In limited aforementioned parts, it did not.

But my experience with The Masterplan wasn’t horrible, so this review shouldn’t end on a bad note. Here are some fun facts to perhaps get you to look into the game for yourself in spite of my ranting: Cars can explode if shot enough. It’s awesome. You can hijack police cars to escape. You can revisit heists, leaving room for mistakes without forfeiture of al chance at 100%-ing the game. Oh, and there’s a little secret at the “Suspicious Alley” anyone remotely interested in this game will enjoy. I wouldn’t have found out how to unlock it without some internet help. Thus I offer some spoiler-free assistance: Before going to the Suspicious Alley, while on the heist-select menu screen, hit pause and you’ll see a little ghost button. Click on it and then go to the Alley. See what happens. It blew my mind and was a definite highlight worth experiencing.

The Masterplan is available now on PC, Mac and Linux through Steam, GOG, Playfield and Humble Bundle for $19.99.

[review]