If you have played a video game within the past couple of years, it is entirely likely that the game had a story. It is entirely likely that you have also run into a prominent issue that comes up rather frequently in the industry as of late, the illusion of choice.

Narrative driven video games have become a hot commodity in the industry over the past couple of years. Stories have been evolving in video games as rapidly as graphics or gameplay, with titles producing works that rival and even surpass big budget movies. Video games provide the immersivity and choice that is lacking in the movie industry, while simultaneously managing to draw in hardcore and casual fans alike with the variety of different type of games that fall into the genre.

While games have always told a story, recent products have begun to market user choice and branching stories as gameplay mechanic pivotal to the game’s enjoyment. These stories encapture fans with meaningful narrative and relatable characters, then give them influence over how the story plays out. As a result of these branching narratives, it would reason to believe that each choice would elicit an individual ending, or at least have a slight effect on a similar ending. Instead, we see a lot of games that throw tiny pebbles into a river, not big stones, making tiny splashes instead of branching forks with multiple paths, creating the illusion of choice.

My first experience with games like this was the Mass Effect Trilogy, which to this day are still some of my favorite games of all time…with an asterisk. Never before had I heard of a game where important characters could die. Never before had I played a game where the choices you make carry over into the next game via save files. Never before have I been lied to as blatantly as I was with the end of the series. I get it, endings are hard to do, especially trying to create multiple endings that make sense.

The problem is that Mass Effect was market heavily by the notion that every choice matters and could mean the difference between one outcome or another. Yet the ending to this hundred-hour long epic trilogy consists of three linear choices, Good, Bad or Neutral – better known as the Blue, Red or Green endings – all of which were available regardless of previous choices. All the characters and the choices that were made were completely invalidated by the lazy end to the narrative.

While the endings were certainly bad (I can’t reiterate that enough) they were a construct of the linearity that is necessary for sequels. To be able to make a sequel, a base point is required, which means that everything has to converge back to one point. If you killed Wrex in Mass Effect, his character is replaced by his brother Wreav who has a nearly identical role and dialogue.

The same can be said for almost every important character that dies. Essentially if you made a choice that kills a plot driver, Bioware creates a similar character in the next game to take their place. If this wasn’t the case then Bioware would have had to make about five different games for the price of one, with no guarantee that some fans will even play through enough to see all five. This is why the Fallout games are not direct sequels, the choices made in the previous games have no effect on the turnout of the sequel.

Chrono Trigger is one of the earliest examples of a game with branching storylines and is also one of the best examples of a game doing it correctly. The game contains well over 10 different endings and is one of the first games to ever feature the New Game + mode. The mode allows players to continue to play the game after completion with all their items, status, etc. and unlock otherwise unstable endings. Chrono Trigger is arguably the basis for which many of the games we see influencing the narrative genre today take their own influence. A huge reason this game has stood the test of time since its 1995 release is that there weren’t any plans for a sequel, so the writers didn’t have to worry about tying in the endings of the game so they could fit the next incarnate in the series.

The market for the modern era of gaming currently revolves around sequels, with games like Assassin’s Creed and Call of Duty releasing a title every year. While they may saturate the market, those games are also the most profitable. On top of the money, the games make at release, the reliability of the existing fan base and already having the assets available to build the next game results in a product that essentially pays for itself.

So while it’s easy to say that studios should create more unique IP’s like Until Dawn, the risk involved in creating the product isn’t worth it if the studio can’t profit enough to stay in business. It’s the reason why Telltale games have been profiting off the current structure they have for their games for around four years.

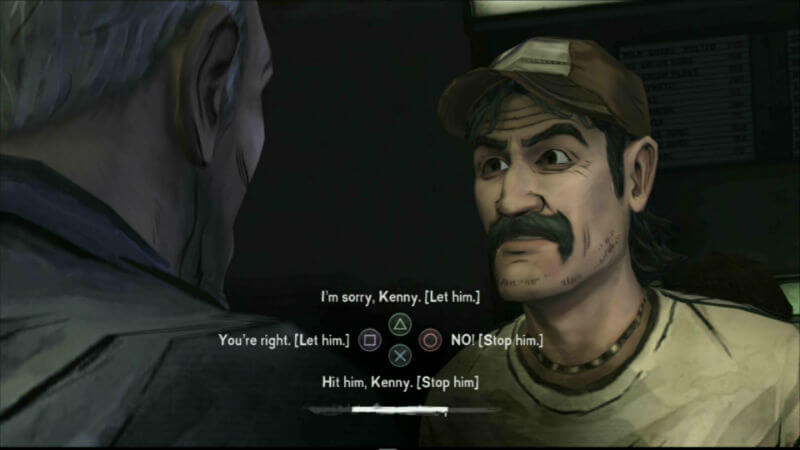

Telltale’s the Walking Dead – much like the studio’s other games – is a series that is solely driven by its story, as the gameplay is limited to point and click and quick time button events. The rest of the game is spent choosing between dialogue options that, each representing different emotions, that will influence the other characters feelings towards the main character. This was Telltales first mainstream success – after similar games like Back to the Future and Jurassic Park flopped – and an indicator that their point and click genre had a market.

While the story was excellent and took place during the height of the Walking Dead television shows run, it revealed Telltales specific method of storytelling leaned heavily on the illusion of choice. A couple times throughout the game, there will be an A or B type choice that could end with one character living and the other dying. Regardless of the previous choice, the character that was saved will inevitably die (usually off screen) without the ability to save them again. Aside from that annoyance, the important events down the line are even more linear, as dialogue is almost identical no matter what choice is made. The worst example being the stranger’s anger toward Lee and Clem regardless of whether they stole from him or not, which was the whole reason for the confrontation in the final act.

Despite the flaws in Season one of the Walking Dead, Telltale’s biggest problem (aside from a broken engine) is that their games are considerably short, so creating different endings seems like it would be feasible and would warrant replayability. Instead, they created a second season riddled with the illusion of choice and repetitiveness, while simultaneously managing to negate the emotional impact of the first seasons ending. Much like the Television show, I could care less about the next season because it simply feels like the creators are milking it at this point. These mechanics have only gotten worse with every Telltale series, as the aforementioned sequel bug sunk its claws into almost every one of the company’s IPs.

The illusion of choice in gaming comes from a good place at heart, a lazy place, but a good one. A good story should elicit an array of different emotions and should never be predictable. It’s why books and movies are so interesting the first time around, you don’t have any idea what’s going to happen. The issue with games is that they can be played through multiple times and since it’s not entirely predetermined like a book or movie, each choice presented seems like it would lead to a different outcome. As a result, while the choice the first time around seemed to add a lot of tension to the situation, replaying those choices reveal that it is a constant, no matter what choice is made and really cheapens the result.

It’s my hope that games will stray away from the use of illusion of choice and it’s usefulness to create sequels. I hope they will instead focus on creating original products and stories that help move the industry away from the stagnant and redundant era of sequels, spinoffs and sequels to spin off that it currently finds itself in (much like the movie industry).