Some of my favorite games of all time have been Open World (Sandbox) games like the Witcher 3, Grand Theft Auto V, Saints Row, Far Cry and far too much more to list. These games boast massive worlds, with single player campaigns that take hundred of hours to complete. Tack on the side quests, multiplayer and plethora of other activities in the world and the collective time spent exploring these worlds amounts to days, upon weeks, even months of real time. The exercise in crafting these worlds is called worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding is a key element to any story-driven medium, take J.R.R Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings for example. Tolkien has thousands of pages of notes devoted to the world of Middle Earth and even has an encyclopedia of sorts for the series published in the form of the Silmarillion. The amount of time and effort put into worldbuilding is what brings them to life, and is why they contain so many small aspects that can be found so relatable.

In the recent generations, open world games have begun to see a lot more success in both short, and more importantly, long-term markets. A lot of this can be attributed to the fact that this is a lot of replayability involved, as well as the ability for users making their own fun. Grand Theft Auto V has been one of the most popular games on the market for consoles – spanning two generations – and PC since its release. While the single player campaign has a lot to do with that, the extra things players can do in the world with the assets they are given – racing, flying, fighting, etc. – created a whole new experience.

Everyone wants to emulate that success and more open world games have been popping up. But instead of putting effort into these games – like the five years GTA V was in development – many companies see them as an opportunity for a quick buck in a popular market. This results in games aren’t built around the worlds like the successful ones have been, but instead are built after the fact, as a way to prolong the game experience.

Usually, they can be created in a short amount of time, using assets from the previous iterations – which is why sequels have become more common as well – and putting a new coat of paint on them. Add a new story, some unique gameplay elements and obviously a different name, and you have a new game. As a result, these experiences are filled with repetitive missions, bland stories and a lot of desolate terrains.

My most recent experience with this unnecessary open world phenomenon came with Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Wildlands. The Ghost Recon franchise has a long history, but this is the first game in the saga to implement the open world aspect. Previous games in the series focused on the military cohesion of a group of four and included unique features like Sync shots. Though Wildlands carries no overarching story elements from its predecessors, it still carries the same fundamental theme and gameplay aspects. So even though it’s not a sequel, it borrows a lot of the same elements from the previous games- like sync shots.

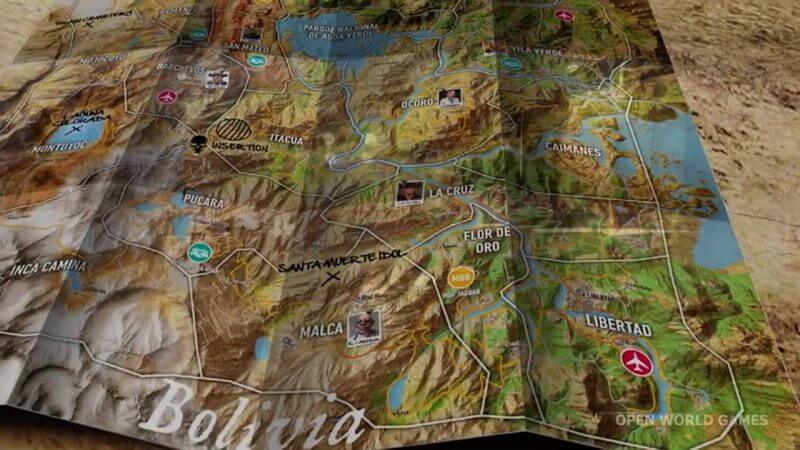

Since it was announced, Wildlands selling point was that combination of Ghost Recon attributes with an open world aspect, instead, it ended up feeling like a generic third-person shooter set in a sandbox. While the scope of the map is certainly impressive and even beautiful, it’s also surprisingly barren. What first looks like an expansive, open Wildland (roll credits) of Bolivian jungle and terrain, quickly turns into repetitive scenery and reused assets. Half of the map is either empty jungle or mountains that serve literally no purpose other than aesthetics or game lengthening. There is no distinct appeal to any area in the map, no personality, no story to be told through the environment.

In the Witcher 3, the world is filled with the aftermaths of battlefields littered with dead bodies, blood, and swords as a result of the ongoing world. Two Knights impaled by a spear. A soldier, drowned in the river because his armor was too heavy. Though not a single word is uttered about what took place on each specific battlefield, there are different stories to be told on each one, simply by looking at it. A man crushed by a wagon,

In Wildlands, despite being set in a country constantly at war with itself, there is no indication of it by looking on the surface. Outside of armed enemies, the only real distinction that can be made from the landscape and its occupants. The only thing the environment of small huts and dirt does tell us is that the land is stricken with poverty. But it’s no wonder that’s the case, as the civilians have no background jobs at all, they just walk around aimlessly, waiting to get caught in the crossfire and result in the player’s mission failure.

The thing is, this world is actually somewhat enjoyable in the Co-op aspect of the game because just like GTA V, players can make their own fun out of it. It’s kind of like growing up as a kid and being able to enjoy yourself simply having a stick war with friends. It’s not the fact that you are getting hit with sticks that is the fun part, it’s the people around you that make the experience. But take away those friends and all that’s left is sticks. That’s what Wildlands feels like to me.

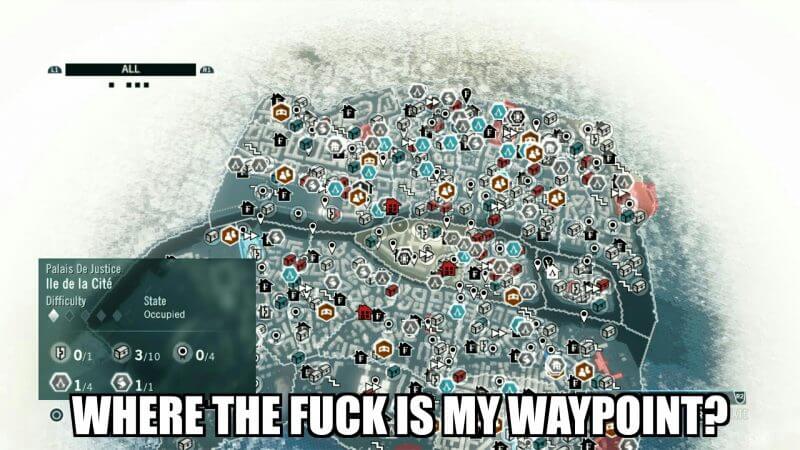

Unless you live under a rock, you know that Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Wildlands was made by Ubisoft, the company at the forefront of the sandbox problem. I’ve been a fan of Ubisoft games ever since Rainbow Six and Splinter Cell, so it pains me to see them go down this path of filler and laziness. While there are some exceptions – For Honor, Rayman, Splinter Cell Blacklist – almost every game that the company has made in the past decade has coerced the open world element into its games. You’d be hard pressed to sift through one of their published titles and find one that doesn’t have an open world, filled with side quests and collectibles. That wouldn’t be a problem if there was sustenance to them. No Ubisoft franchise embodies this element more than the Assassin’s Creed franchise.

Ever since it’s inception, Assassin’s Creed has been filled with huge worlds – divided by loading screens – with sprawling cities, densely populated with NPCs. While each NPC served little purpose other than aesthetic appeal, they still added to the atmosphere, which was the game’s main selling point. Climbing the buildings and looking out over the vast cities was certainly a breathtaking experience.

But as the franchise rolled on, they did little to add a personality to their landscapes, and instead added more buildings and collectibles. That’s not to say that some of their buildings weren’t impressive and there wasn’t research behind some, as many mirrored their real counterparts, but the game’s original appeal of climbing a building and admiring the view lost its meaning after so many games.

What once was a linear story, also began to branch off, filled with side quest and other additives – though the series has always loved its meaningless collectibles – that didn’t really add much to the games. To be fair, that statement doesn’t apply as much to the Ezio saga (Assassin’s Creed II to Revelations) as the Italian and the world he lived in were actually interesting. But with the end of that saga, also came to the end to a boring, and confusing, overarching plot line started from the original that took place in the real world.

What was to believe to had been the grand purpose for collecting flags, feathers, animus fragments and a number of other additives eventually led to the character killing himself and the series somewhat starting anew. When it comes down to it, the Assassin’s Creed games have become 20 percent story, 80 percent tacked on unnecessary additives that “add” to the world.

The new games still lightly cling to that original story as a means of creating a new game each year. And each one of these new games isn’t filled with unique individual stories, despite the different times to which they travel, but are instead filled with sneak, follow missions, fetch quests and repetitive variations of beat enemies in this territory.

And again, these could all be somewhat more bearable if there was any sustenance to them at all and if they added to a story. Instead each game just ends with Iso or Juno (I can’t really tell who is who anymore) making an appearance in the real world version – which is also now limited to a husk of an avatar working for Abstergo that Ubisoft doesn’t even name – who eventually states something vague that reveals there is going to be another game so she can do it again at the next one (and so on and so on).

What makes all of this even more frustrating is that Nintendo has managed to prove that it is totally possible to modernize a previous game franchise – I mean it’s essentially their business model at this point – and throw open world elements. Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild has drawn a lot of comparison to its N64 predecessor Ocarina of Time for its gameplay and structure. But no one is stating that it’s a complete rehash or rip-off of the original, simply reusing similar elements from Ocarina and pawning off under a new name, instead, it builds upon the things that the original did right, improves them and adds other things.

Breath of the Wilds’ world also feels alive, like it’s handcrafted to a specific mold. If Link is wandering the world and hears an NPC getting attacked by monsters, it’s because monsters attack anyone, not just link, that just makes sense. There is no reward for saving them, other than the thanks they give. There’s another situation where Link is standing on the edge of a bridge, and a passerby tells him not to jump, essentially that suicide isn’t worth it. That doesn’t need to happen, it’s not a cutscene where he’s placed on the bridge, but it can happen because this world was meticulously built to feel alive.

Be it in singleplayer or multiplayer, the sandbox fad is ruining a lot of possible games by milking the experience with empty words, repetitive missions, and meaningless collectibles. As a result, franchises like Assassin’s Creed aren’t selling what they use to, and don’t nearly have the fan base they once did. It’s my hope that publishers and developers will eventually stop forcing open world games onto ones that don’t warrant it, simply as a means of prolonging the game’s runtime.