The premiere of Humans aired June 14, 2015. Its fourth episode aired July 20. I thought writing a review prior to this would be a moot point without knowing where the season would go. Anything can happen at a story’s beginning, but it can’t properly be judged until the latter half of the story begins to unfold (unless it’s just that bad.)

Recently, I wrote an article on why you should be watching AMC’s new sci-fi series Humans. I am now going to shamelessly reverse my opinion and explain why you shouldn’t watch Humans.

I won’t lie, I enjoyed the first three episodes. Enough happened to keep my interest, and some plot points emerged that promised to take off, flesh out characters, the world, and overarching themes. The way the show brought the silent terror of intelligent robots into the home was particularly stirring. I can compliment the show as I can compliment most AMC series: It makes viewers ask questions and doesn’t numb your brain to watch.

But episode 4 proved something to me. I couldn’t pinpoint what it was before, it being so early in the series, but something always seemed missing from the intrigue, the synth-conspiracy, and the synth-induced, crumbling family ties featured in Humans. There was some kind of depth issue. But after four episodes of its escalation, I have it at last. The plot, the sense of “oh my gosh, and then this happened and then this happened and then—” supersedes character development in importance in Humans.

Wait… a show about humans, and they don’t even slow down to delve into their characters and build up to the big moments? Let’s talk about that for a minute.

Successful shows operate off of the assumption of the dignity of each human life, meaning that everything that happens to affect a character’s arc, outlook, and ultimate fate is crucial for good ratings. Even in Breaking Bad, though Walter White was a hugely unlikeable human, he was constantly developing as a human being. He had motives, disagreeable or not, and they tugged him in multiple directions, compelling him to one action or another. It’s how viewers connected to him even as he spiraled downward… and sideways and every which way. Humans does not operate off this assumption and doesn’t bother to do the same with its cast. It has numerous characters with great potential—the son of a scientist who has wires in him and wants to give consciousness to all the synths, hiding those who already have it. But we don’t know why he does it, and I want to meet him before I care about his vigilante quest. There’s a crippled woman whose dependence on her “young, male” synth disrupts her life with Pete, her husband and a detective. Why are they on such rocky ground, aside form the synth’s presence? Can’t we talk about that more before in episode 4 she suddenly tells him, “You don’t make me happy anymore… I want some time alone”? Also, the Hawkins family. With their three different-looking kids (each of whom has one (1) defining trait), they lead a complicated existence that seems to survive in purgatory (how?) rather than hang together with any legitimate bonds. Those bonds are never practiced or explored on-screen but are used to back-up plot lines, like Laura wanting to get rid of the family synth.

The show discusses the differences between humans and synths, especially in terms of relationships, true. But it fails to distinguish living, human consciousness from “living,” synth consciousness. This being the first season of a show about conscious synthetics walking among us, this seems like a poorly ambiguous way to launch into the mid- or end-season. Television is all about becoming invested, and not addressing this issue sets all of the show’s other ethical commentary in an existentialist and absurdist universe where ultimately, nothing has meaning, not if the human’s relationships are no more than something that can be programmed into robots. I can’t applaud the show for this ambiguity. It avoids a huge moral question and deprives the show of that urgency that would take it beyond interesting and curious, like something seen in a cage at an old-time “freak show.” The show seems like it wants to say that all life is valuable and operate off of that assumption, but it doesn’t distinguish what “life” is. Humans appear no more special than smart, “feeling,” robots, so why care for any individual human? Or any of their quests?

I know a huge point of the show is that a small group of synthetics have consciousness and feelings, and that what “life” is can get confusing when synthetics like this are made. It’s alright for the characters to be confused about what this “life” means, but for the show to be successful, its opinion on the matter should be clear. And I think it is. But by being existentialist, they’re trying to exist in a Joker’s world (Batman Joker) where only chaos dictates what happens. Hard to connect and care when that’s the case.

Rarely does Humans pause to let the emotional impact of an event linger. For instance, the Hawkin’s family’s work-devoted mother, Laura, finds her youngest daughter becoming unhealthily attached to the family’s new synth. More ominously, the synth seems to be becoming attached to the young girl, which synths aren’t meant to be able to do. At the end of an episode, the synth kidnaps the girl, violating all synth codes of conduct. Cut to the start of the next episode, and the girl is back home. This plot choice isn’t the problem. For me, the issue is that after this, the mother, Laura, who has been suspicious of the synth from the start, begins to believe either she is paranoid and crazy or that her synth is broken. Which she already pretty much believed. And the only actions she takes based on these new developments are to question the synth and argue with her husband about it. Tension escalates (the synth took the girl!), then deflates (and the kidnapping got us where?).

Even when Laura tries to return the synth to the store without her husband’s agreement, and the synth saves her child’s life by stepping into traffic, everyone (synth included) ends up back at home without any noticeable shifts to the status quo. Laura and Joe are as unhappy as they were at the start of the season. Laura’s suspicion of the synth continues, but it doesn’t change form. Just when it seems a character is about to evolve after trouble brews, the show seems to forget that the trouble ever frothed over and introduces a new conflict instead. It relies on things happening in six story lines that could be completely isolated and make little difference. It relies on things happening for the sake of having things happen, not for how the characters react or change as a result. To me, that doesn’t make a good show.

Simply put, no one feels truly human on the show. (Ironic, isn’t it?) They seem more like replicas of what humans may or may not do in these scenarios. I don’t blame the actors. But this is also just my reading of the show. Though IGN also agrees. Maybe things will turn around after episode 4. Maybe Humans is still finding its stride.

There are still great aspects of the show that ought to be mentioned. A rogue murderess synth, Niska, has gone on a rampage against humans. She discovers a synth battle arena (essentially synth chicken-fighting) and goes there to destroy the humans and liberate the synths. This moment expanded the show’s world enormously, just as the existence of synth hackers and modders did. The issue remains that after her destruction the status quo wasn’t shifted at all, but at least she got some wicked nail-gun action in against the human hostage she takes to escape.

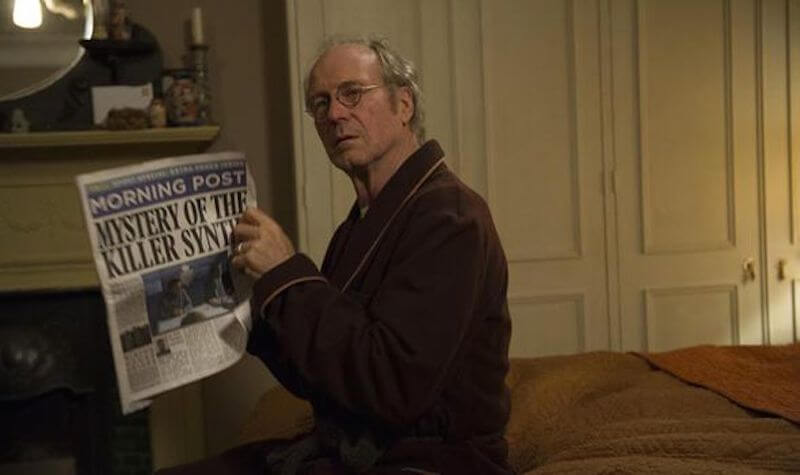

Another story line has an original creator of the synths (seen above) living under guard by a hospital-assigned synth he doesn’t want. Meanwhile, he’s hiding his old synth that he had while his wife was still alive and who can sometimes recall memories (data) of her. The emotional core of this story has yet to be plumbed fully. In episode 4, only this man’s old job as a synth creator and his bid to thwart his new synth’s orders were focused on. Certainly these are crucial bits of information, and it brought his storyline together with that of the synth-modifying vigilante. But it still felt like we were being jerked around by a flashy door-to-door salesman trying to tell us how marvelous his product can be.

[review]