Skip To...

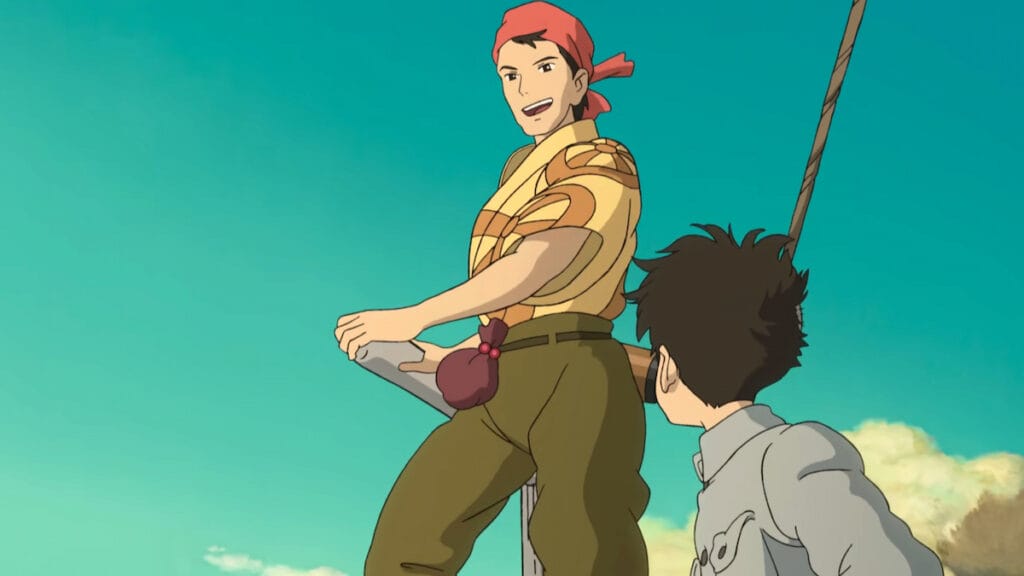

You would be forgiven for feeling lost after watching Studio Ghibli’s The Boy and the Heron. You may feel spellbound by the brilliant, lively journey but confused by the narrative. The Boy and the Heron doesn’t hold your hand or explain itself. The film falls in line with Studio Ghibli’s structure, which rarely aligns with traditional Hollywood storytelling. Instead, the film utilizes what is called Kishōtenketsu, an unorthodox storytelling method that explains The Boy and the Heron.

The Boy and the Heron Shouldn’t Be Explained

Many overstate the need to recount the plot beat-by-beat. That’s probably what you’re looking for from an article with “Explained” in its title, but it’s less helpful than it seems. You get the basics from the trailer. Mahito Maki loses his mother in a hospital fire. His father marries her younger sister, Natsuko, taking Mahito to meet his aunt/stepmother at her mansion in the countryside. A suspicious gray heron, the sharpest of the home’s supernatural elements, harasses Mahito. Mahito wounds himself with a rock, trapping him at home. The heron requests his presence in an ominous blocked-off tower, where it claims his mother remains. Natsuko soon disappears. Armed with a homemade bow and an arrow bearing the heron’s feather, he enters the tower.

Mahito discovers the tower, built by his mother’s Granduncle, offers portals to mysterious lands. He attacks the heron, piercing its beak with his arrow and finding its new weakened form. The heron agrees to be his guide, but a wizardly figure sends the bird, Mahito, and an old servant into a new world. He meets fisherwoman Kiriko and young pyrokinetic Himi. Mahito learns the local food chain, but he escapes Kiriko’s beautiful home with the heron as parakeets threaten their lives. Himi guides him to a hall of doors to other worlds, eventually including the one Mahito came from. Evading the parakeets and their king, they find Natsuko in a delivery room. Violent paper and electrified stones stop their progress, but Mahito finds love for his new mother. Finally, Mahito finds Granduncle and learns about the toy blocks that control his world.

Studio Ghibli Films Aren’t About What Happens

The Boy and the Heron features several conflicts. Few of them end in fights, but struggle is important to Miyazaki. This is his most personal film, exploring his relationship with his mother and creative partners. The film uses a storytelling method called kishōtenketsu, which is regularly tied to Ghibli projects. Kishōtenketsu is simpler than it sounds. It breaks stories into four parts, similar to but distinct from three-act structures more common in the West. Kishōtenketsu features an introduction, a new development, a twist, and a conclusion. Mahito mourns his mother’s loss and struggles to acclimate to his new life. He explores the mysterious but enticing world around his new home. Almost every detail between his entrance into the tower and his return comprises the twist. Then, the door closes, and Mahito is back home. The journey wasn’t in the tower but inside Mahito’s heart.

Some denigrate the structure for its shifting focus. Remember critics accusing My Neighbor Totoro of being boring? That accusation lands on stories that put less weight on what happens than on how it changes people. Mahito learns from Granduncle after experiencing the blocks. He finds a way to put aside his selfishness and live for others. The Parakeet King, enraged by his seemingly childish activity, destroys the block tower. Mahito returns home, learning Himi is the younger version of his mother. The story ends where it started, but Mahito is a changed young man.

The Boy and the Heron, like most Ghibli projects, is about many things. The brief vignettes Mahito experiences are lessons taught to a growing boy. Thematic mirrors capture everything from climate change to adolescent sexuality, consistently pushing Mahito to his new destination. It’s a world of symbolism and education, but the direct events are uncritically presented and frequently untethered. The film is a coming-of-age story. Mahito evades killer animals and braves immense danger. There’s a different version of the story that could exist. A version in which Mahito instead learns the magic system and takes over Granduncle’s position with the wisdom of his bloodline. But looking for an explanation is missing the point. Instead, learn from experience, as Mahito did.