Available on: Microsoft Windows, OS X, Linux, iOS

Developer: 11 bit studios

Publisher: 11 bit studios

Genre: Action-adventure

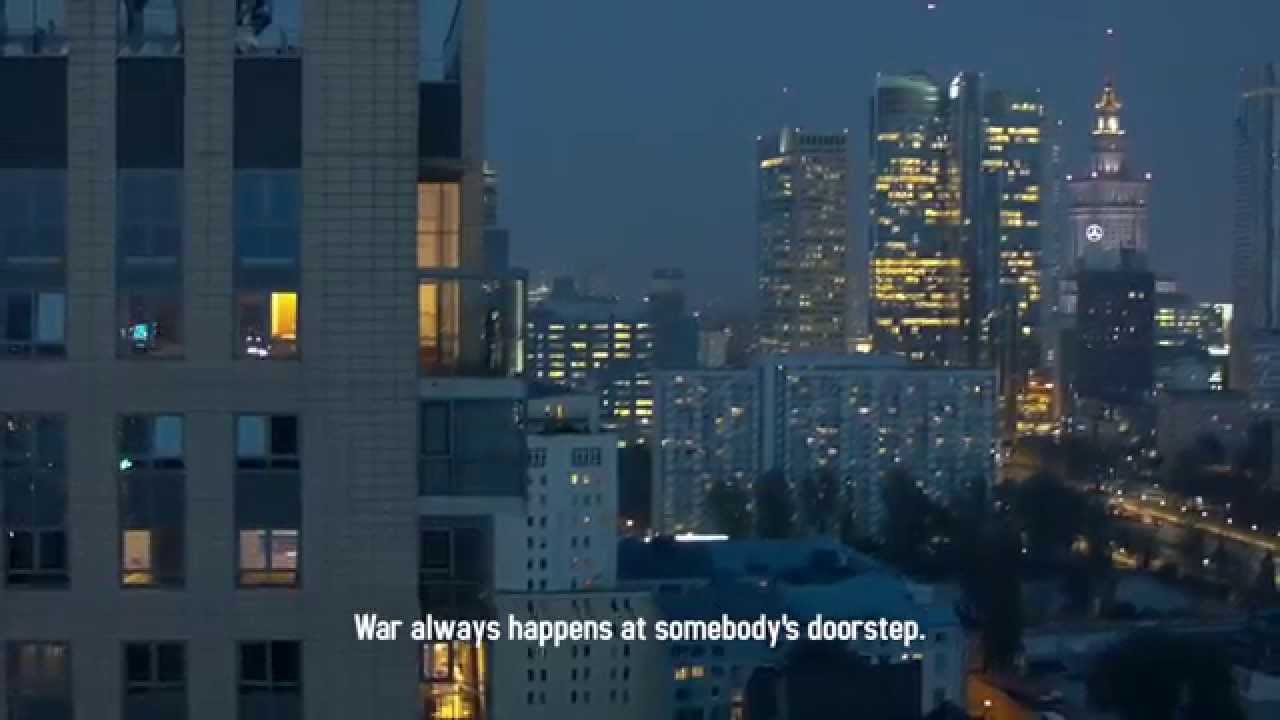

The largest update released so far, 1.3 opens up a new path into This War of Mine’s heart of darkness with a scenario editor called “Write my own story.” With these new tools, the city of Pogoren and its inhabitants bend to your will as you alter aspects of gameplay and story. It opens an entire new way of undergoing this harrowing (and traumatizing) game. What only felt like it became an autobiographical experience before can now more truly be one.

“Define new civilian,” the new character creation tool, allows players to name, choose a profession and physique, and upload a personal photograph of themselves, friends, family, or anyone else as a playable character. As if struggling to keep your survivors alive and facing their unglorified, unwarranted deaths is tough enough in This War of Mine—truly, as it quotes Hemingway, “In modern war… You will die like a dog for no good reason.” Now, with the character editor, players can personalize gameplay to reach a new level of immersion and investment. Should a character die—say, your mother—it’s likely those left alive won’t be the only ones in a “broken” state of paralysis.

But as with the game itself, with these new traumas come new opportunities for growth.

There’s a reason the game has been received so warmly and with so much success. The character creation tool only utilizes its already successful abilities as an evocative simulation. By encouraging reflection on the ways we as humans treat one another, on morality in the face of impending death or misfortune, it forces the unanswerable questions to be asked, “What’s the point of it all, anyway? Was there a purpose to any of their lives or deaths? Is there any hope when reality is that bleak? How do we choose to cope with it?” Adding character creation only awakens these important questions more directly in players’ real lives.

As for the remaining aspects of the 1.3 “Write my own story” update, they’re arguably ambivalent—sometimes seemingly more good than bad, sometimes more bad than good.

The rest of the update grants control over the number of days until ceasefire (between 20 and 80); the intensity of the conflict (low, moderate, high); which locations will be available at night and the type of people (or lack thereof) to be found there (generally thugs or innocents); when winter will come (early, halfway through, late), its harshness (mild, moderate, severe), and its duration (short, moderate, long).

It’s impossible to complain about controlling the difficulty level. But having a say over the other aspects seems to showcase some of the game’s weaknesses.

While certainly diversifying players’ experiences of the game by handing them a way to try out various scenarios, the gameplay editor does so at the expense of the elements of chance and risk. After a few plays through the game, location layouts (including locked doors, obstacles, and NPC movements and dialogue) become recognizable. Soon after, they’re memorized. Merely reading the descriptions of what each site contains on the night-select city map becomes for the cautious and knowledgeable player a decision of “I will gather this, this, and this tonight successfully, which means I can make this, this, and this tomorrow, and thus be in a position to do X the next day, and X the day after.”

So the only thing left to mystery is what will happen with the bandit raids at home overnight. Once the player overcomes that obstacle, the march to the finish has few hiccups, no real worries—little urgency.

To test whether this was true and an easy victory possible (and to ensure I wasn’t touting criticism out my back-end), I created a scenario with the hardest settings: high conflict, a city map full of bandits, and an early, severe, long winter. The result? I survived. This was my fifth play-through, and I had only survived once, on my fourth. How? I finally knew what to expect, whom to expect when and where, and what to trade ahead of time.

Is “Write my own story” necessarily a bad thing? Not at all. It’s actually quite fun. After all, chess is a highly formulaic game, and it’s a classic. Whoever deducts the best strategy ultimately wins, and with great satisfaction.

In the case of “This War of Mine,” however, because the opponent is an electronic system and not a human, it’s obviously more of an “I finally beat this Sudoku puzzle” satisfaction than the excessively-emotional, panic-dissolving relief of “We survived!” (which is otherwise typical of This War of Mine). Indeed, the only time you fail, once you figure out a game strategy that works, is when you fail to realize you’re being shot at or make some silly oversight, so it’s a bit like being the old man from Pixar’s short film “Geri’s Game.” You play against yourself. And is that really a satisfying victory or failure? (To be fair, because it is an electronic system and not a human opponent, it’s more understandable that it can be taken advantage of. Yet the extent to which it can be still seems too great.)

The point of the game is living in conditions where nothing is certain, after all.

What’s revealed in the scenario editor is how many NPC types are available at each location. Usually, it’s one or two, and occasionally three. And each NPC group has its own repetitive dialogue and movement patterns. (The Brothel, Military Outpost, and Garage, among others, are the same even night-by-night no matter how many times you visit). I often expected the loaded son with the sick father at the Garage to be murdered at some point by looters, but he always pulled through (to my mixed relief and annoyance.)

One thing that would be great to see put into the game, particularly in locations where scavengers are prevalent, is supplies disappearing between visits. Even if only on hard mode. That would make leaving items behind even more difficult and force players to take more risks. It would also tempt players to view all NPCs as potential threats, even those who come seeking aid during the day, and make all scenarios more realistic, considering the amount of scavenging going on in the city. Moreover, since one main point of the game is sacrificing the well-being of some for that of others, giving the player more reason to not trust or help NPCs can only deepen and complicate the morals of the experience. By having supplies disappear as other people scavenge them, players must face their own responses of greed and spite and suspicion accordingly. Every decision carries more weight and comes from a more immersed place.

One of the best moments (that I’ve had) in the game so far was at the Looted Gas Station (one of two new locations, the other being Old Town). On your first visit, you find a corpse. A cue shows up that, when activated, reads:

More instances like this occurring occasionally and not in every playthrough would be a fantastic direction for the game to go next. That’s the true diversification of scenarios the game needs (I believe). With the two additional locations added in update 1.3 and two new music tracks, it already has the perfect framework to build off of.

Because let’s be honest, this is already a bloody brilliant game. (And if you want to get it, it’s available on Steam and the Mac App Store.)

And if there’s one thing that never stops amazing me, no matter how many times I dive into this messy war of mine, it’s the number of corpses strewn across the landscape. They’re all so easy to miss, with the camera zoomed out. But they’re there. What’s beautiful is the game’s quiet brutality of making you look for them.

What do you think and have you played this game? Let us know in the comments!

Purchase This War of Mine Now on Steam!

[review]