If you haven’t already, go read Ryan Griffith’s insightful article “Women And Video Games.” On what is a very taboo subject, Ryan leads a balanced investigation. So I don’t write this as a refute. Rather, my thoughts are that, as a woman, I can build on what Ryan has already dug into. I’ll attempt to articulate the problems as I, a woman, see them, and perhaps offer some unique insights and solutions of my own. I obviously can’t pretend to speak for all women. This is solely my opinion. Still, I’ve tried to take an unbiased yet distinctly female view on this subject, if that’s not too taboo to say, and hopefully the result will be productive.

And like Ryan, I can’t cover it all. It’s a huge topic. But I can cover some. The stuff that matters to me most. (I apologize in advance. This is a bit of a long one. But I feel it’s worth tackling.)

Women play video games. Women like to play as women in video games. Sometimes men play as them, too. But especially young girls, they really like to play as women; the characters let them be the big woman they aren’t yet. Just like Ryan’s sisters, in hand-to-hand fighting games like Street Fighter and Virtual On, I always chose the girl characters, even if I was terrible with them, even if it was only a robot that looked remotely female, and even if I had no idea how to use them. Unlike some games, fighters like Mortal Kombat always seemed to have female options, and I always took them. But I don’t think that’s what we need more of today to fix the “women in video games” inequality issue. Hear me out. Because here’s the catch (and I knew it was one as a child, too): My decision to play these girls was exactly like choosing the red token for a board game, or the hat for Monopoly. I didn’t care about the game, or the end goal, or even the character herself. Just the appearance of this stand-in figure. It satisfied some compulsion to possess, and that was all.

The take-away point: They never had any significance for me. Sure, it was a way to express myself, and that’s important in and of itself. Yet girls like Chun Li (characterized by only those blue ribbons and a high voice) weren’t the ones who stuck with me and made a difference in my life all these years later (though I’m sure she did to some who found her to be a round personality). If we’re to talk about having more women in video games, I think we first have to talk about what types of women we want to see.

I think we need female characters with substance. Memorable female characters. Not the female version of Aiden Pearce from Watch Dogs, for example, not a female equivalent. Unique ladies.

But there’s a catch even in this scenario that makes this “solution” not so clear-cut. (There’s always a catch, but I don’t think that’s bad—I think it means some serious thinking is being done.)

Growing up with all forms of media—books, TV, film, video games, internet (LOLcats)—as a regular part of my life, I consumed stories about female leads whose sacrifice and adventurous spirit brought health and prosperity to their ailing loved ones. In particular, the television show Alias, starring Jennifer Gardner as top spy Sydney Bristow, captured my hopes and imagination, and to this day I find hints of Sydney in my words and actions (though I remember none of hers)—and, admittedly, in my fashion sense (which is little to none, so I could use more influence).

Women like the ones in these stories had an incalculable influence on me, and who’s to say why? All I know is that in part from their example, I’ve been forming myself ever since. Without these fictitious women in my life, my character may or may not be exactly what it is today. Their examples saved me from making many mistakes; likewise, they’ve helped me come back from mistakes I did make, when I needed a hand up. Or when I need to be reminded how to get myself back up on my feet. Becoming the woman I am was so much easier when I had someone else’s footsteps to follow instead of having to carve my own. They helped me learn how to understand the world, or learn how to understand understanding the world (to get meta). In particular, though, I found power in these females. They were strong women, and they did leave their imprint on me. And more women like them should be in games to encourage other girls and women in the way I’ve been inspired. Real, round characters who come to life in the imagination, making up a home and settling there like the little angel and devil on your shoulders.

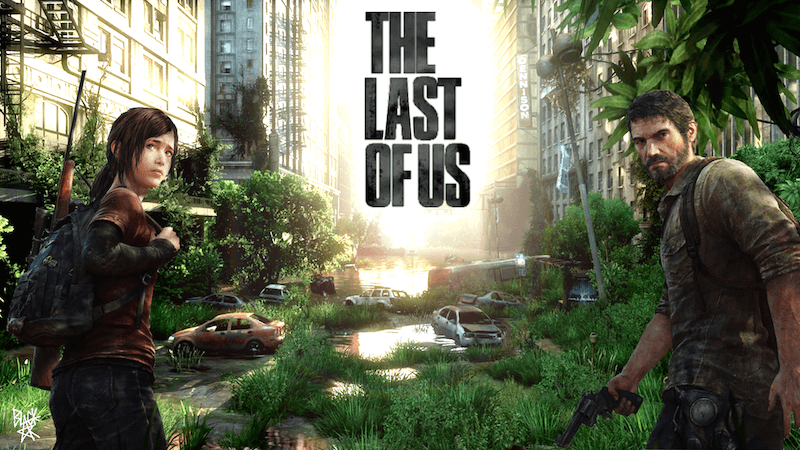

But that doesn’t mean representation has to be 50-50, or match the 52%-of-gamers-being-women demographic that Ryan cited in his article. Certainly I connected to these characters woman-to-woman, but I didn’t connect to them because they were women. I also connected very strongly to the male lead of Shadow of the Colossus, to Mario in all the games, to Lee in Telltale’s The Walking Dead, even Thomas in Thomas Was Alone (and he’s a rectangle for crying out loud). I connected to these men far more strongly than I ever did the flat, female lookalikes in other games, and had true influence on me as well. So I connected to the women I did because their stories were good, their characters fleshed out, and these only possible because their particular stories called for a female perspective. It’s the story the author envisioned, wanted to tell, and the person, not just an un-humaned gender, the author wanted to tell it through. I saw that and loved all characters, male or female, in the mysterious way that anyone falls in love with a character. I fell because of who the author makes them and how I relate to what the characters do and how they behave—not because we share the same gender. Such a detail isn’t and never was an end-all-be-all trait for me to relate to them or being inspired by them, as a child or as an adult. Suggesting anything to the contrary is somewhat insulting.

Would I love to see more women in video games? Hell yes! Would I sacrifice good stories for the sake of having a 50-50 representation of genders in games, or even an upswing in female characters to match the women who make up 52% of the gamers who Ryan reports play in the US alone? Hell no. I want stories to have a protagonist of the gender that the developers and writers feel works best for the game and story. I’m adamant about this. To try and force a gender on a character is to misrepresent something in the life of that character, and a falsified character is someone no one can get behind. It’s why those failed female-led games hit Ryan so hard and with such a sense of disappointment, I’d guess. Because it’s sad that developers might feel the need to falsify female characters just for the sake of having them in a game as a gimmick to make them succeed. Sorry, but in the long run, those aren’t the games whose female leads make an impact on one, the market, and two, the consumers. To create games for a specifically-female protagonist is to make a game whose purpose and end are encompassed in the creation of the character herself, and no character can be a worthwhile game on her own. Sorry (not sorry) ladies.

(Yes, I know there might be real sexism out there and that some developer may indeed want to keep video games an “all boys” club. I’ve never personally heard of or met any of them, but nonetheless, I’m adamant: That problem is solved by letting such exclusivity root itself out over time, as it surely will, not by drowning them in poorly-made female-led games that still represent women poorly and make boys-clubbers just laugh anyway, right?)

But now it’s time for another catch.

A huge part of the outcry involved in the women-in-video-games argument is as Ryan put it: “Why is it that in most story driven games, women are pushed to sidelines and are portrayed to be a sexy, damsel in distress, or a two dimensional character that do something cool during a cut scene but then aren’t a playable character? Why do they always appear weaker than their male counterparts?”

I answer that that’s a laudable sentiment, but it’s not that simple. Having women “pushed to sidelines” in video games and “portrayed to be a sexy, damsel in distress, or a two dimensional character” are very different things. Believe it or not, the former is the bad one. It implies intention. The others are just traits a story can choose to inflict on a non-main character, male or female. For instance, Bandage Girl from Super Meat Boy—she doesn’t bother most people. She’s the quintessential damsel in distress, the two-dimensional character, but she serves a purpose in Super Meat Boy. It’s just the game mechanic that works best for Super Meat Boy. It’s nothing against women. (And there’s still something to be learned from her and Meat Boy about helping loved ones in need, which was the message I and I believe most women took away from them without even thinking about it as well.) “But it happens in almost every game!” you argue. I agree, if women are being “pushed aside” because of bias towards them, that’s horrid. But if it simply isn’t necessary to the game to have complex females in lead positions, it oughtn’t to be forced. (In those cases, “pushed to the side” is misleading language. Hence why the matter isn’t so simple.) Again, I don’t think damsels in distress or two-dimensional characters is something that needs to be done away with; in most games, they serve a simple purpose, and like in Super Meat Boy, that purpose comes across. I can see complaints against poor incorporation of women in cases like Ubisoft’s, where they claimed female characters are too expensive to generate, being called out. I agree, it smells like bullshit. However, from a very idealist point of view, female-led games should be made as often as the creators want to make them and as the market demands them, not by force of some notion (however well-meant) of proportionality.

So now the complicated matter of “gender inequality” as it fits into video games. To be frank, I have never liked the term “gender equality.” Yes, if you asked me, I would tell you that there are more men than women in games. Again, I’d love to see more playable women, even ones who aren’t bad-asses or “strong,” as people always applaud. Do I think the low number of featured women in games equals gender inequality? No. Equality isn’t in numbers alone.

Where the inequality comes in is when a woman, even just one, in story-driven games are so inaccurately portrayed, or in other words, dehumanized (in a degraded way, not two-dimensional way, which are different; the first is an offense, the second is a very necessary story mechanic). I can say with fiery, vehement distaste (from more years of personal experience than you will care to know) that dehumanizing a woman by reducing her to her value as a body is abominable. She’s more than “boob jiggle physics” and a “juicy booty.” Treating her as anything less ought to be fought against, particularly in video games where those women truly “come to life on the screen.” In unequal proportions women are more often stereotyped and exploited than their male counterparts. That’s wrong. Not because of the unequal proportions. It’s that it happens at all.

Anytime anyone, male or female, is dehumanized in that way in a game, it should be frowned upon. Rather than just fighting against sexy-breast-beast portrayals of women in games, we ought to be fighting for the dignified portrayals of all characters, whenever and however created. Men and women can have sexy traits, personality, even a sexy persona; but that shouldn’t be the entire pivot-point of their character.

And we should be fighting, if we want it, to say, politely, “Hey, developers, we would like to see some more games like Tomb Raider. With cool ladies in them. Smiley face. Thank you.” Request logged. We can make the market work; it’s all about having our voices heard in the right way so that our words, ideas, and motives are understood as well.

I personally cannot wait for the next installation of Square Enix’s Tomb Raider. The new Lara Croft inspires me to be fit, explorative, and to find ways to follow my heart. Seeing Daenerys in TellTale’s Game of Thrones thrills me and inspires me to be kinder to those less fortunate and who feel like they have less of a say in the world than I do, even if she isn’t a playable character.

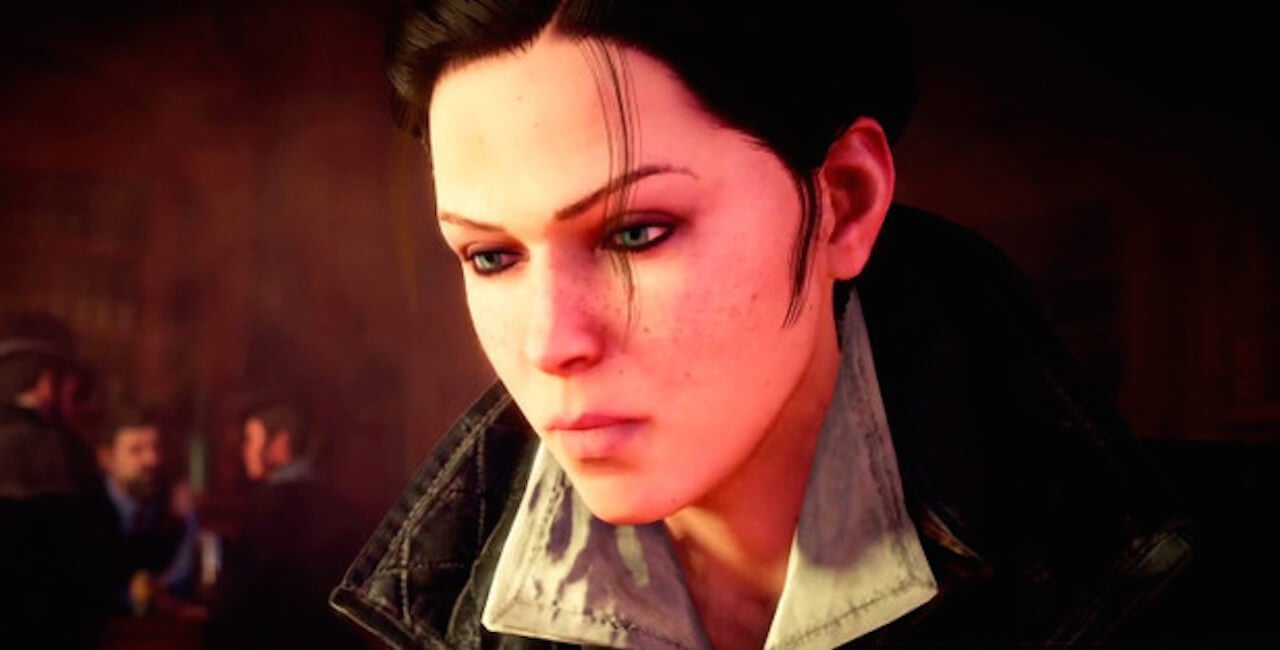

But as a woman in this messy affair, I know there’s the danger, too, of characters like Evie Frye of Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed Syndicate. Nothing is certain, but all the news and hype coming from and circulating around the game, especially in light of Ubisoft’s explanation of why female characters haven’t been featured in the series prominently before, seem to indicate that Evie is an attempt to satisfy cries for a playable female character. So far, after E3, I’ve heard nothing but praise of her and how awesome she is, and maybe it’ll be the case after all that she rocks the stage as Evie, not a noticeable We-Needed-A-Woman-Character-To-Save-Our-Asses figure. After watching E3, I myself am rather convinced that she will be her own real, round character, and I couldn’t be happier. But we should all be weary of those times when by focusing on a character being a strong, specifically-female presence, companies will forget to make a girl more than her gender and less than what I think the public is truly wanting, under it all. More Ellies. More Laras. Equally decent presentation, not necessarily identical proportions (although in theory something near that would be cool).

I hope I’ve done justice to this argument in this matter. If you disagree or agree, please feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments. This is a completely safe area, and with such a hot topic as this, it’s important for ALL voices to be heard. (Just try to make sure we can year your words through the voice you use!)

And with that, this is Ripley (nope, T, but she sticks with and influences me), signing off.