Version tested: PC

Also available on: PlayStation 3 & PlayStation Vita, Linux, iOS, Android,

Published and Developed by: Mike Bithell

(WARNING: Some spoilers ahead.)

And into the portal we go, upwards and to the right.

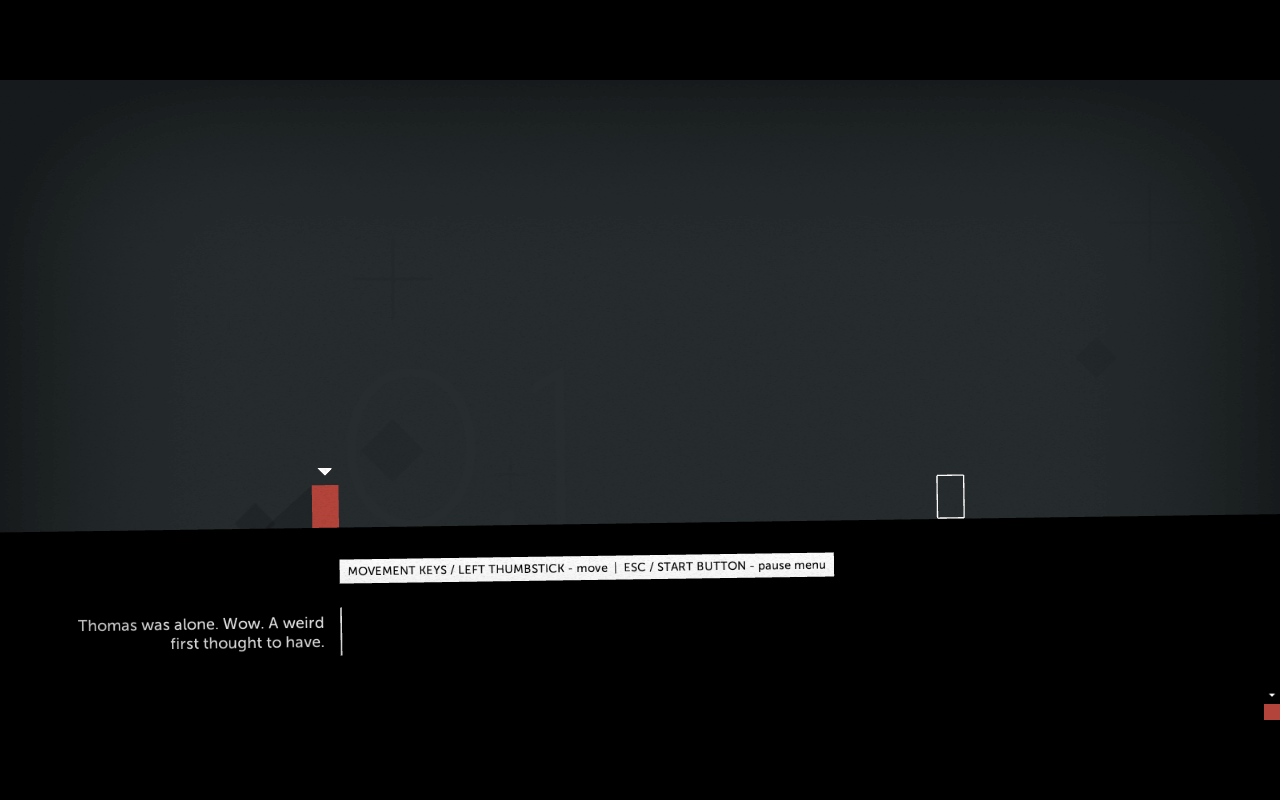

Three years since Thomas and crew gained cognizance and set out to fill their bleak world with friends, their crowd of supporters continues to grow. Why? Like Thomas found out, the more people involved in the mission, the merrier its success. Not only does Thomas Was Alone make for a fantastic single-player game, but it’s brilliant to enjoy with others; in fact, it’s nearly impossible not to share it with others. (Hence this article.)

I had seen the game in its entirety back in October of 2013, yet in all that time my affection for it hasn’t dimmed. Thomas Was Alone, as an extremely self-aware reflection on “Why video games?” and “Why the world at all?” and a million other loaded questions, has all the criteria to become the equivalent of a literary classic, a game people repeatedly come back to. It’s already well on its way.

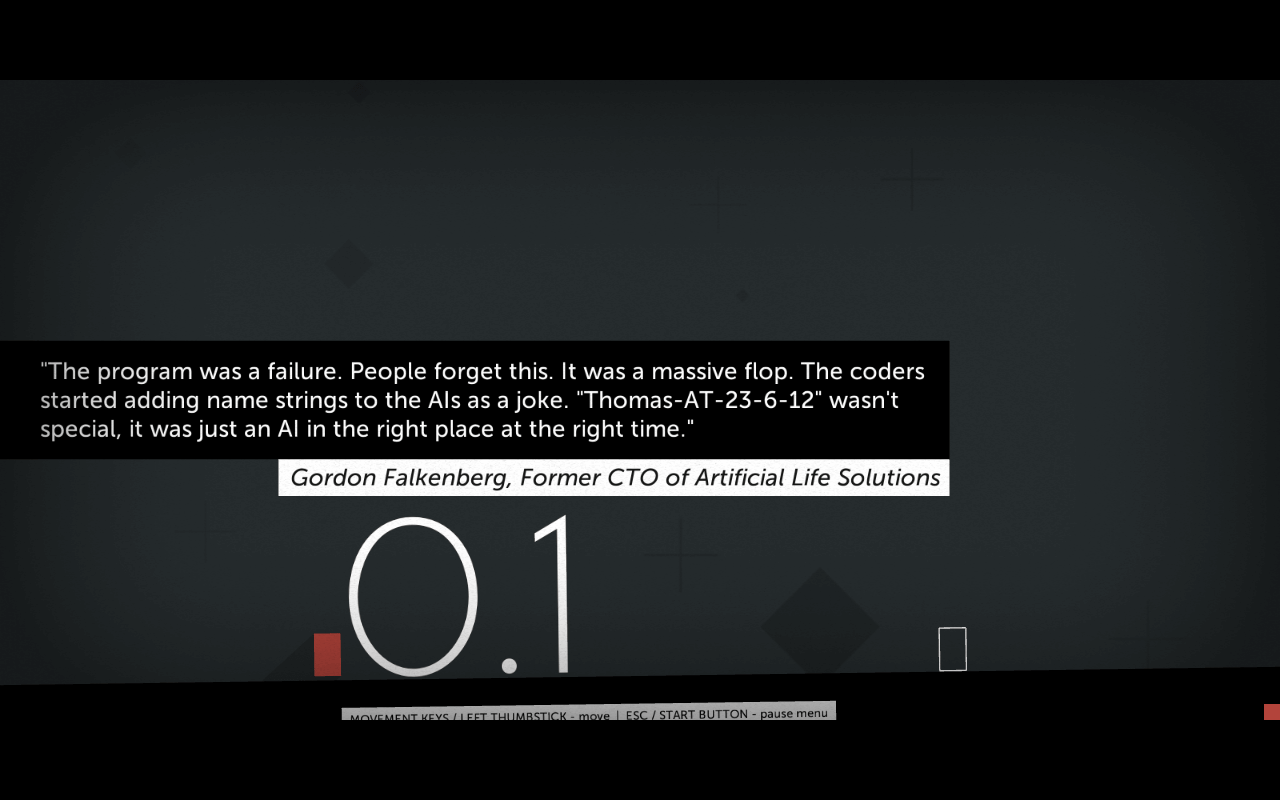

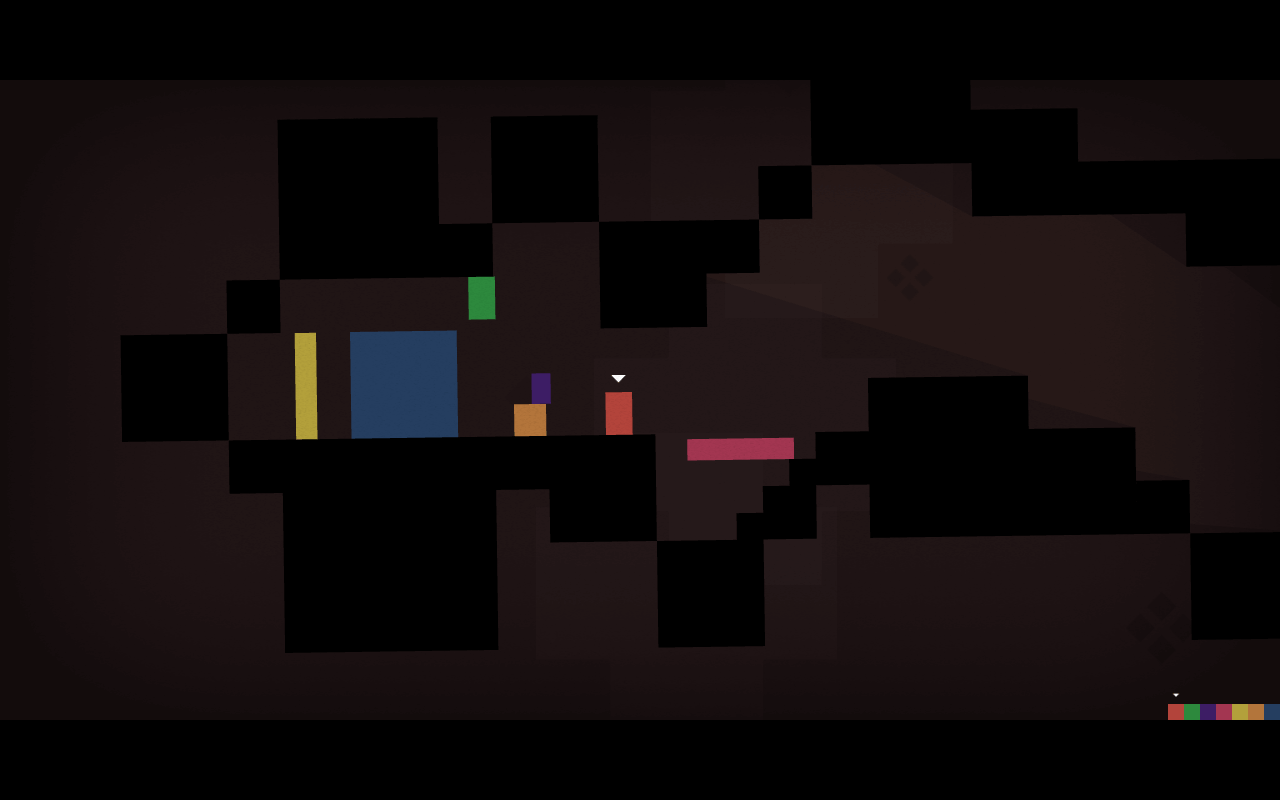

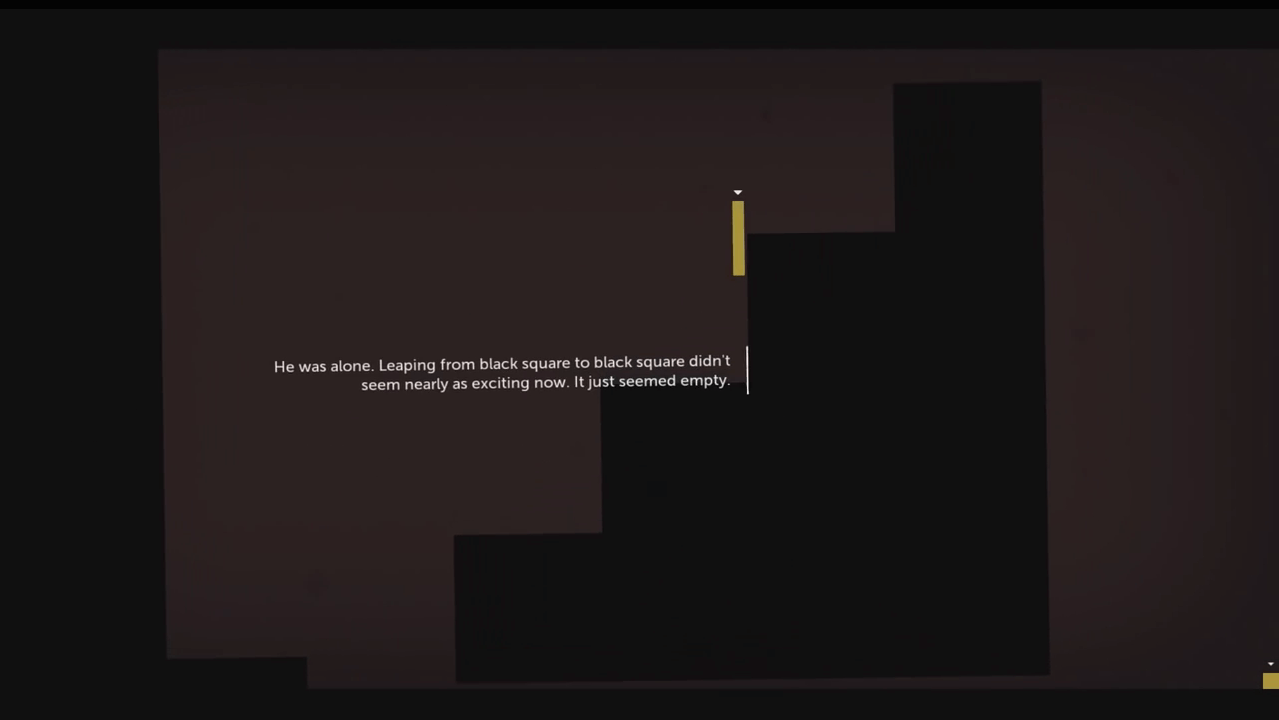

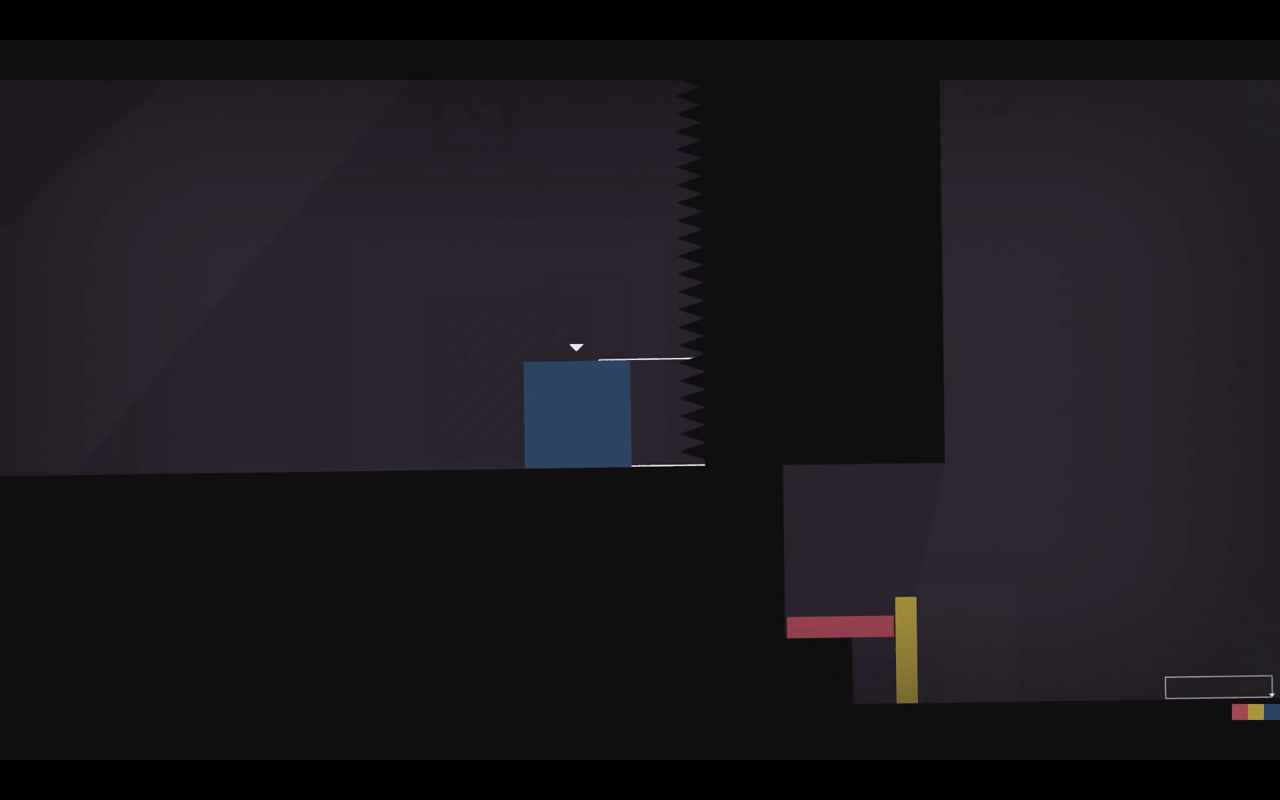

“The more people involved in the mission, the merrier,” I say. But Thomas and his friends are voiceless squares and rectangles. The maps they run across are constructed entirely of black blocks, and only the backdrop and occasional pool of water seem to have any gradation whatsoever. Our friends are encased in a bleak world full of “contrived spaces, these intentionally obtuse paths and puzzles” that Thomas rightfully grows sick of. But these black plains and obstacles act cleverly as building blocks for character development, the fostering of teamwork and nurturing of appreciation of individuals’ talents. Plain as they are, these environments aren’t isolated from the story; the characters are as restricted by and aware of them as we are ours.

In perhaps one of the most self-aware moves in (relatively) recent gaming history, the characters acknowledge the implications for themselves of their surroundings, and they strive to find a better world to live in—namely, ours. The programmer comments that appear at key story points give credence to Thomas’s transformation into cognizance and action, and they pull our attention deeper into Thomas’s caged-in world, knowing a better one does exist for him. Suddenly, it seems not only like Thomas we’re playing as, but ourselves.

We’re drawn along a parallel journey to Thomas’s to understand what makes us care about anything, real or virtual, and are given hope; why we exist at all when there’s suffering and separation and what we intend to do with our existence and about our problems; why we would ever make sacrifices for others and why the world is designed the way it is, sometimes gorgeous, sometimes inexplicably cruel:

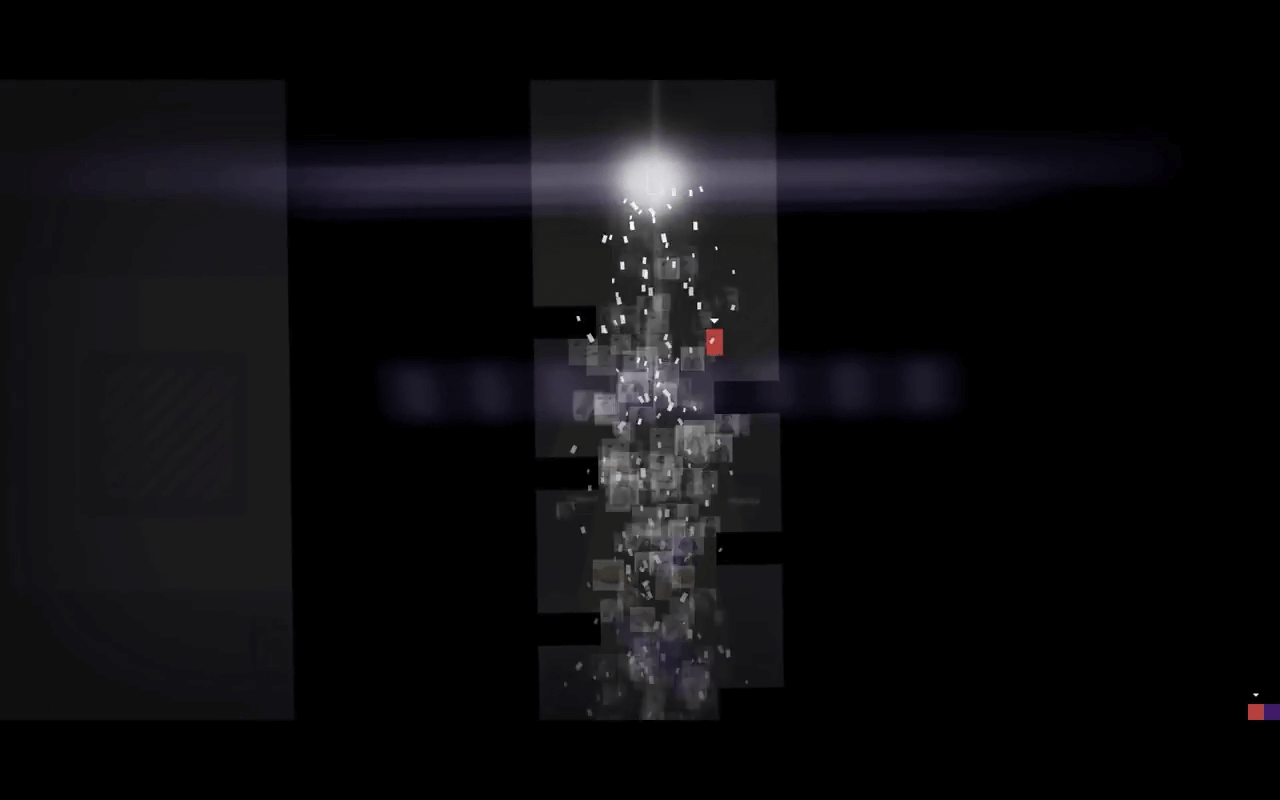

And as the levels progress and Thomas and his gang uncover a way to allow other AIs to escape, even if they can’t, the maps become more erratic, less closed off, more free of constraints. Thomas and gang begin to have a real effect on the world, and being able to aid and witness it is nothing short of empowering. (Involuntary fist-pump.)

Essentially, Thomas Was Alone is a retold creation story. The realization of a meaningful, existing self—what a blindingly motivational fact to slow us down and make us relearn how we play games! And to exist! The possibilities! Dare I say it? The story brims with Christian themes that, even if you aren’t Christian, you can likely get on board with: the value of self-sacrifice, of the existence of free will that creates opportunities for good and evil in equally profound measure, and the equality of all human creatures. “But Thomas and crew are rectangles!” you shout at me. They are, but they’re characterized in entirely human terms. Who doesn’t find themselves relating to Laura and James’s fear of being considered strange and weird? Who hasn’t felt John’s pride at being the best jumper, or burned with Chris’s buried resentment at being squat (I feel ya) and (seemingly) unremarkable (ouch)? Really the only thing about them that isn’t human is their physical, pixelated shapes. They’re more human than most human video game characters, which of course makes them so powerful, even for wee shapes.

The intimacy achieved between player and shape is insane. You will cry (inside) with sorrow and joy, you will “ship” them (ha!), and you will want to hug them and tell them it’ll be alright, you are special. You have a role to play.

And like it or not, this isn’t Call of Duty where enemies are just targets. Here, enemies perform a crucial role in the grand scheme and cannot be so offhandedly thrown out, expressing a frustration that really does exist for us players. What to do with bad people? It’s like Gandalf said, “My heart tells me that [Gollum] has some part to play yet,” and he did. Thomas Was Alone gives us free range to explore that idea’s (and many others’) complications.

Interpret this game as you will. I award it five stars for having so many plausible interpretations and fostering thought, not thoughtlessness (though I do relish a good shoot ’em up as much as the next chum). Many games fail to have even one and fade from memory in time. Thomas, not so.

This game stands as proof that story is far more important than graphics (cough, The Order: 1886, cough). The review published by The Telegraph in 2012 words it best: “It’s a fascinating example of great writing being able to stir the imagination, building personality out of the simplest visual tools and sharp language. Each quadrilateral character in Thomas Was Alone has its own worries and traits, narrated with real delight, wit and verve by Danny Wallace,” (who won a BAFTA Performance Award for it). “And David Housden’s wonderful, understated score lays down an irresistible aural backdrop to the basic but beautiful visuals.”

Truly, limitations as an indie become its strengths, as Hoggins claims.

So as you sail across each map as long-jumping John or bounce atop Laura to reach higher platforms and ultimately each level’s end portal, using nothing but the environment, the occasional button, and each character’s innate abilities to get there, it’s impossible not to root for these little guys, all the while growing more confident in our own unique talents. (Feel the power!)

And the more people sharing in the experience, the louder the rooting and the gasps. If you’ve already played through this game, might I suggest doing a massive playthrough with friends? You’ll never run out of things to say, and a great time will be had by all.

If I had one criticism, it’s the system of switching characters by scrolling through them or by number select. Because the arrangement on the character-select bar kept changing depending on who was in each level, it was difficult to select the wanted character on the first scroll or number press. Consequently, the camera flew dizzyingly all over the screen from Thomas to Chris to Laura to John to Claire to James before I finally settled on Claire. But that’s forgivable enough.

Thomas Was Alone reinvents the usual, monotonous gameplay of a puzzle platformer to teach us life lessons. And that’s why this game is still relevant today. Its questions are timeless. Its mixture of story and gameplay and altruistic themes, fresh. It’s wit and daring twists, charming.

So, have you played the game? Do you have a response or want to discuss what you liked, disliked, or your own experiences with Thomas and the gang? Please do drop some lines in the comments! Be there or be square.

[review]